The Business of Navajo Weaving in a Down Economy

Shirley Brown with her handspun and handcarded Two Grey Hills masterpiece. If you want to talk about intrinsic value, this is a good example.

Several people have asked me how Navajo weavers are doing in this economic downturn. That’s not an easy question to answer because Navajo weaving is sold in several ways, each affected differently by economic conditions.

Most Navajo weaving is sold as Native American craft work. Although this market has slowed, it has drawn strength from the perception that the items sold have an inherent value that cannot be erased like, say, the value of a share of Lehman Brothers stock. While Navajo weavings may not appreciate as quickly or as steeply as some other types of investments do, with care they most certainly retain a lasting value. Most traders amass a collection of work, kind of a trader 401k, that helps to fund their retirement. Trader Hank Blair’s mother, complimented by an appraiser on the depth and variety of her collection remarked “Well, if something didn’t sell in two or three years, I just took it in the house….”.

Some Navajo weaving, of course, is sold as fine art by weavers like D.Y. Begay, Barbara Jean Teller Ornelas and Morris Muskett, artists who are represented by galleries and whose work is shown in museums. This market seems to have been somewhat affected by financial trauma, but once again is buoyed by the intrinsic value of the work. There is always, it seems, a market for the best of the best.

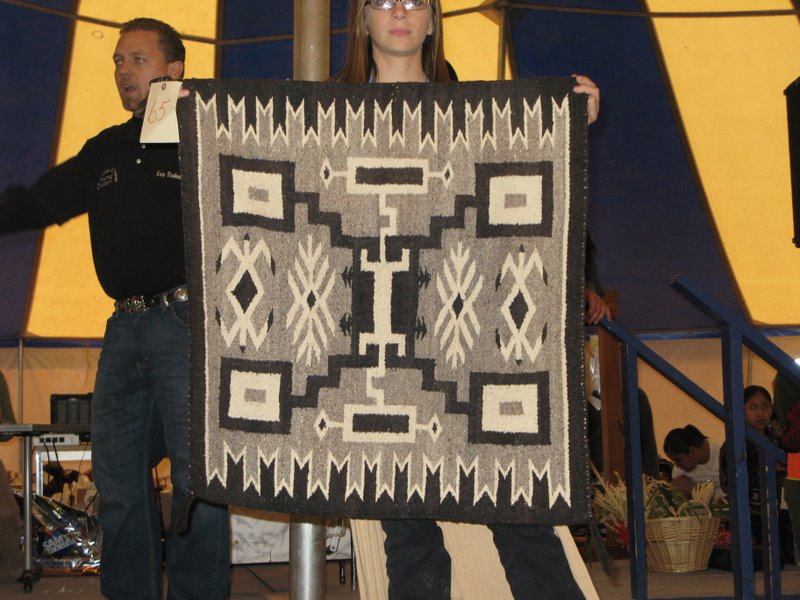

Under any economic conditions, one of the major issues for Navajo weavers is getting the best price for their work as quickly as possible. The opportunity for a weaver to sell a rug to a local trading post has been declining for decades as the number of on reservation trading posts has dwindled. I talked with traders Bruce Burnham and Hank Blair about this recently and they said that they could only think of seven trading posts still buying weaving that were actually on the reservation. There is still a very active trading economy in towns like Flagstaff, Arizona and Gallup, New Mexico, places that are referred to as “border towns”, but the concentration of a few large buyers and the large number of weavers drives down prices in these areas. Weavers also travel as far as Durango, Albuquerque, Phoenix and Tucson to sell their work. The growth in the number of Navajo rug auctions over the last few years has helped to give weavers a new outlet for their work, and it’s one that so far has weathered the current economic seas. R.B. Burnham and Company has built their auction business up to some 15 auctions per year, returning over $800,000 to the consigning weavers so far in 2008. The Crownpoint Rug Auction also offers a dependable monthly auction, usually offering over 200 rugs, returning 80% of the purchase price to the weaver.

Navajo weavers wove through the Long Walk and the Great Depression. Ninety-year-old Anna Ashley remembers selling her weaving by the side of Route 66 when there was no other market for the work. She raised her family with the money that she made from weaving, just as Emily Malone is raising hers today. As the late weaver Stella Cly would say “Now with the comb, you are not only batting a design together, you are also chasing away the evil spirits of poverty”.